One Writer's Old New York

Notes on life at the dawn of the 20th century.

New York City in the first decade of the twentieth century was a very vibrant place to be. There were problems, to be sure: three-quarters of the population lived in tenements, wealth was concentrated in the hands of a very few, the government was corrupt and workplace conditions were deplorable. But there was also tremendous optimism that these problems could be fixed, and a belief in the power of the individual to make a difference.

Perhaps President Teddy Roosevelt best represented the attitude of the day, when he declared, "Believe you can, and you're halfway there." To my mind, this made the period an appealing setting for a novel. It's a time and place I'm happy to return to again and again, that never stops surprising me. On this page I'll be sharing, in no particular order, bits and pieces I've discovered during my forays into Genevieve's world. To comment on these entries, or to see more about New York history, my books, and the writing process in general, connect with me on Twitter @CuylerOverholt or visit my Facebook author page.

Ten Ways to Die in Old New York

The city presented some intriguing ways to die during this period, just waiting to be mined by the murder mystery author. I write about ten of them in this post for the Strand Magazine.

Can the Dead Communicate with the Living?

That was a hotly debated topic back at the turn of the twentieth century. Although our Puritan forebears didn't countenance such a notion, the massive influx of Irish, Scottish and other immigrants to America in the second half of the nineteenth century had brought with it an abiding belief that the boundary between the living and the dead could indeed be crossed, an idea that was particularly welcome to the many who had lost husbands and sons in the Civil War.

In Celtic tradition, Halloween was considered the most propitious time to receive communications from the dead, usually in the form of predictions about the future. But as Spiritualism took root and spread over the decades, any time became a good time for a seance.

It might seem odd that Spiritualism would flourish during the Progressive era, a period noted for its adulation of science and the scientific method. But in fact, the extraordinary scientific advances of this time had led many to believe that the spirit dimension was simply one more mystery that could and would soon be cracked, just as the mysteries of electricity, radioactivity and wireless telegraphy already had been.

Investigators were accordingly dispatched from various societies of psychical research to evaluate purported physical manifestations of spirit, some intent on debunking the mediums who produced them, others eager to prove that they were genuine. Of course there have always been con artists willing to part believers from their dollars, and the ranks of turn-of-the-century mediums were full of them, making the search for authentic cases more arduous than many had expected. Investigators encountered "spirit hands" made of stuffed gloves or carved animal liver, "ectoplasm" consisting of various combinations of egg white, soap, gauze and potato starch, "floating" trumpets suspended by threads, and ghostly apparitions built out of wire and muslin. And yet, despite the many disappointments, popular belief in mediums remained strong.

"The Most Thrilling Event"

The first London Olympics were held in 1908, after the eruption of Mr. Vesuvius (and the consequent need to divert reconstruction funds to Naples) knocked Rome, the original venue, out of the running. Although Italy lost the chance to host the Games, it could take some satisfaction in the performance of one of its own at the London marathon event, as reported by The New York Times on July 24th:

“It would be no exaggeration in the minds of any of the 100,000 spectators who witnessed the finishing struggle of the Marathon race ... to say that it was the most thrilling athletic event that has occurred since that Marathon race in ancient Greece, where the victor fell at the goal and, with a wave of triumph, died ... Dorando [Pietri], an Italian who was not thought to have a big chance at the event, reached the Stadium first in a state of complete exhaustion ...

Partisanship was forgotten [as] people rose in their seats and saw only this small man clad in red knickers tottering onward with his head so bent forward that his chin rested on his chest ... He staggered along the cinder path toward the turn like a man in a dream, and dropped to the ground. According to the rules of the race, physicians should have taken him away, but the track officials, lost in their sympathy for such an effort lifted him back to his feet and with their hands at his back gave him support. Four times Dorando fell and three times after the doctors poured stimulants down his throat he was dragged to his feet, and finally was pushed across the line with one man at his back and another holding him by the arm.”

The official assistance caused Pietri to be disqualified, although Queen Alexanda presented him with a silver cup at the closing ceremonies in appreciation of his extraordinary effort. The gold medal went to New Yorker Johny Hayes, son of an Irish immigrant family who worked as an assistant manager at Bloomingdale’s sporting goods department, and one of only three American men to ever win the Olympic marathon. Pietri ran against Hayes in two rematches over the following year, winning both.

The heroic Italian competed for three more years before retiring to run first an unsuccessful hotel and then a car garage. Hayes was promoted to manager of the Bloomingdale’s sporting goods department upon his return from the London games. He was a trainer at the 1912 Olympics, and later worked as a subway tunnel sandhog, a gym teacher and a food broker.

Tin Pan Alley

Ragtime, according to its modern champion Terry Waldo, was America’s first and most unique contribution to musical literature, and has influenced almost every type of American music since. Launched by Scott Joplin’s hit song “Maple Leaf Rag” in 1899, the form became wildly popular in the U.S. and Europe over the next twenty years. A variation of the popular march, it got its “kick” from syncopation (the displacing of the beat from the music’s expected meter), which gave it a natural, spontaneous feeling that appealed to the youth of the day.

In fact, one schoolgirl was so smitten when she heard a young man playing ragtime at a local moving-picture theater in 1909 that she agreed to elope with him on the spot. Her parents, the New York Times reported, were “deeply affected”.If you ever get a chance to attend one of Waldo’s ragtime performances, don’t pass it up; he’s a very talented musician and entertaining host. The second best option is to stop by his website.

The Dollar Princesses

In 1874, Jennie Jerome of New York City married Lord Randolph Churchill, 2nd son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, triggering a wave of marriages between European aristocrats and the daughters of successful American businessmen and speculators. By the first decade of the new century this trend had reached a peak, inspiring the 1909 musical comedy "The Dollar Princess" (poster at left). By 1915, 454 American brides had crossed the Atlantic.

One of the most famous of the dollar princesses was Consuelo Vanderbilt. Consuelo's domineering mother Alva insisted, among other things, that her daughter wear a painful back brace to improve her posture, and feigned a heart attack when Consuelo refused to marry the 9th Duke of Marlborough because she was in love with an American suitor. The marriage to the Duke eventually went forward, terminating in divorce.

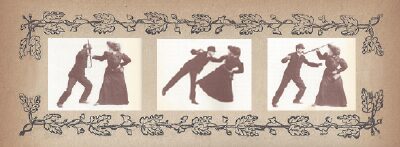

The Feminine Art of Self-Defense

As the "Modern Woman" became more independent, venturing out on long bicycle rides and solitary walks through the city, she also became more vulnerable to assault. “What, then, can be provided to her that will be formidable to a foe, yet absolutely safe as far as she is concerned, and ever ready at hand?” asked the New York Tribune in 1904. The answer, the newspaper suggested, was a new, weapons-grade hatpin, “sharp as a needle and hardened at the end so that it can be used with deadly effect as a dagger,” with a handle designed to allow a firm grip.

A year later, jujitsu was the new craze among New York society women, made popular by President Roosevelt and practiced by his daughter Alice. A sub-specialty of this art was the “umbrella defense”, which combined foot movements from boxing, passes and thrusts from fencing, and the ju jit su concept of meeting strength with weakness. A variation was taught by Dr. Latson in New York, whose pupil is pictured above.